I can confirm in my hospital that we use a multiplex test that tests for all sorts of respiratory pathogens, including COVID and influenza. Only one swab now. It’s pretty slick.

Welcome to my life. Although my field is not medicine or public health, I deal with these sorts of issues (and teach graduate students how to handle them) on nearly a daily basis. Statistical analysis is an extremely powerful tool in science, but to properly use it one must exercise very clear and careful thinking about exactly what is being tested and even more so be hyperaware of possible confounding influences. Considering that experienced scientists can make major mistakes if they become sloppy, it is dangerous for anyone to employ these methods as a ‘black box’ without really understanding what is going on.

Here’s an example from my own life several days ago. One of my students is investigating ‘atmospheric rivers’, which are plumes of moisture that can generate a lot of precipitation on the West Coast. One question is whether atmospheric rivers are more frequent when El Nino occurs, and with 40 years of data, it is a simple task to count up the number of atmospheric rivers hitting the West Coast during El Nino months and divide by the number of El Nino months in the 40-year record. Similarly, one can calculate the frequency of atmospheric rivers during La Nina months and during months with neutral conditions. So my student did this and found out that atmospheric rivers are more frequent during both El Nino and La Nina conditions. This result was counterintuitive because usually El Nino and La Nina have opposite effects on global weather patterns. Things became more puzzling after I asked the student to calculate the uncertainty ranges for the results and they did not look as I expected from twenty-five years of experience. I began to wonder if my student made an error and asked her to describe the steps of her methods in detail. Then a flash of insight came to me, and everything in the results made perfect sense – atmospheric rivers occur more frequently in winter (the rainy season on the West Coast) but El Nino and La Nina conditions also both occur more frequently in winter (some winters El Nino, other winters La Nina). Thus, the real driving factor was the winter season, and a more sophisticated approach would be needed to tease out any independent influence from El Nino or La Nina.

Getting back to interpretation of facts, I will point out that my student held the implicit and unspoken assumption that El Nino and La Nina months were evenly distributed throughout the calendar year, and this colored all of her subsequent analysis. I don’t fault her for this since she is a student after all, but it is my job to teach students to avoid errors like this. I am always on the watch for self-deception – thinking that the ‘facts’ of my statistical analysis are answering my question when they are actually answering a different question, and I warn my students to always consider what confounding factors could possibly come into play and to check for them.

If the data are available, the right kind of statistical analysis can mitigate confounding factors and get an answer for the specified question, but a simplistic approach can lead to disaster.

Edited to add: An implicit assumption in the calculations carried out in the linked article is that the population receiving the vaccine has the same characteristics as the population not receiving the vaccine. It may be the case that it is false to conclude that people are not a hundred times less likely to die if they are vaccinated, but it may also be false to conclude, for the 16-44 age group, that vaccination makes no difference for the risk of death when infected. The author alludes to the possible non-similarity of vaccinated and unvaccinated populations in the sentence The death rate if infected was always going to be higher in the vaccinated groups if most of the vaccinated were those likely to die in the first place. If the people getting vaccinated are different from the people not getting vaccinated, then it may be problematic to draw conclusions from comparison of health outcomes.

Joseph,

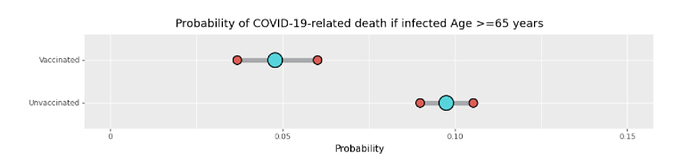

That piece has some helpful information, but the central graph and takeaway are really bad and misleading. The Israeli data he is discussing shows that for people >65 a vaccine causes a 50% reduction in death, if infected. This group has 85% or so of all deaths in the study. And yet he equal weights all of the age ranges (including the range with 0 deaths in the vaccinated group, giving enormous confidence intervals) and concludes that a vaccination doesn’t cause a reduction in death… this is at least as bad as what Tom Frieden texted. This is a classic case where the binned data is much better. I think he is doing this to point out that stats are hard, and it is easy to be mislead by them, but in the process he is misleading a lot of people.

There is loads of evidence that vaccines do prevent severe illness and death if breakthrough-infections occur. It shows up in aggregate data and in more granular data.

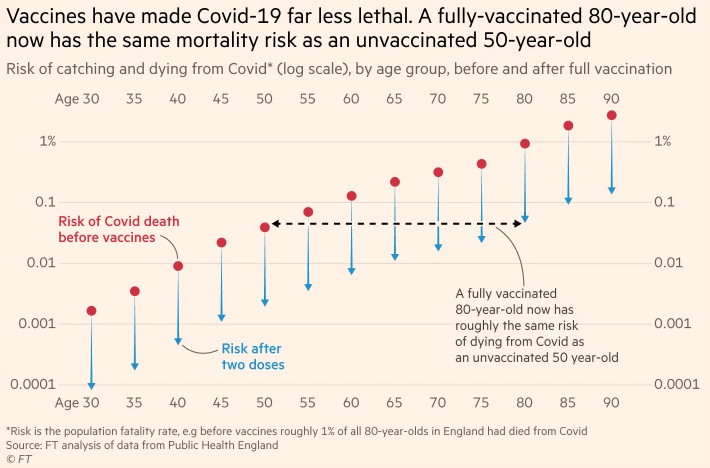

This chart from the FT is using time series data for CFR by age group:

Also, go to any countries with a high vaccination rate and look at a time series of their cases and deaths. Basically everyone with a decent vaccination rate is having a case surge, and not much of a death surge: United Kingdom COVID: 6,117,540 Cases and 130,503 Deaths - Worldometer (worldometers.info)

That chart doesn’t address the question, which is whether there are stacked benefits.

Agreed. This is what stood out to me as the most blatantly missing info in his article.

I used the word “generic” in an attempt to appropriately qualify the statement, but I see it can be read another way. There is no such thing as a generic person, so it’s not generally applicable. Sorry for the misunderstanding.

Part of me wants to say that this stuff is actually not difficult at all because it involves simple differences and ratios rather than, say, partial differential equations or vector calculus. What it does require is very clear thinking about the exact question one is asking and whether the differences and and ratios one uses are actually answering that question or a different question.

Following up on my previous comment, this week my student recalculated the frequency of atmospheric rivers during El Nino conditions compared to baseline conditions with weighting according to the frequency of El Nino across the months of the year. This approach avoids the confounding association of the winter season with both atmospheric rivers and El Nino occurrence, but a new wrinkle came up. Strong atmospheric rivers never occur during summer over California, but El Nino sometimes occurs during summer. Should summer months be included in the denominator? That would make the change in strong atmospheric river frequency with El Nino appear smaller because the denominator would be larger. Or one could exclude summer months and get a larger change.

Here are the questions one would be asking:

- What is the change in strong atmospheric river frequency during El Nino, including those months of the year in which strong atmospheric rivers would not occur anyway.

- What is the change in strong atmospheric river frequency during El Nino, considering only months of the year in which strong atmospheric rivers might occur?

Note that one question is not ‘better’ than the other and there are circumstances in which one would be preferred to the other. The methodology is simple and straightforward, but clear and precise thinking is required.

Of course. Unfortunately stacked benefits have been harder to study and there aren’t great “slam dunk” papers on the effect. This study, Prevention and Attenuation of Covid-19 with the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 Vaccines | NEJM, shows a reduction in fever, duration of symptoms, and days in bed for vaccinated vs. unvaccinated healthcare workers. The population skews young and healthy. But despite having 4x more vaccinated than unvaccinated people in their study they only had 16 infections in the vax group (vs. 155 in the unvaxxed) so the data isn’t all that robust.

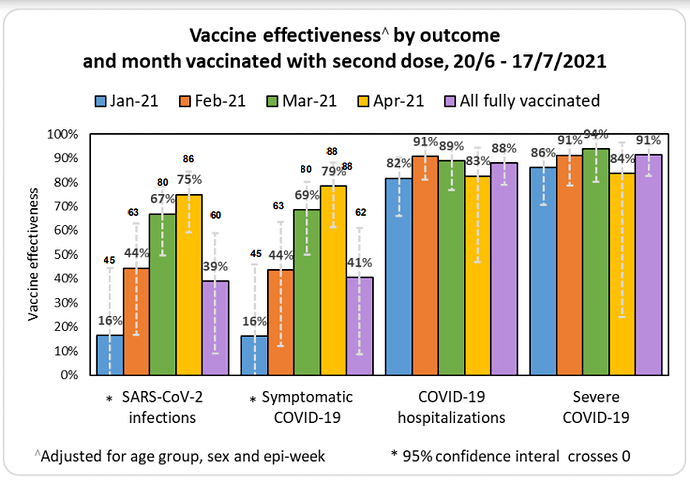

The same large study that RollerGater picked apart has released follow up graphs that shows a major decrease in mRNA vax effectiveness against infection with Delta over time, but which shows maintained protection against severe illness and hospitalization. This would seemingly be impossible if the vaccine didn’t attenuate the severity of the illness. As far as I know they haven’t published the dataset yet. ריכוז נתונים על מחוסנים בשתי מנות עד לתאריך 31/1/2021(דיון מ 20.7.2021) (www.gov.il)

Of course, RollerGators own analysis shows that in the population where it matters most (and the only bin where the finding is significant), the vaccine cuts the risk of death in half:

I think this is right. The math isn’t that tough, but asking the right questions and thinking clearly is difficult. And gathering the right data/adjusting for the right confounders can be very difficult as well. Add in trying to message the findings in a way that is truthful but actionable to a relatively unsophisticated audience, and you end up with a thorny set of problems.

Yes. And that’s great news!

I’m talking about mask specifically, These studies don’t seem to be a slam dunk regarding those. AFAIK, the CDC can’t show any studies to back its assertion that droplets (not aerosols) spread SARS2. No empirical study found significant effects. The burden of proof is on those who would want to mandate these masks, and so far, it’s pretty sketch.

“Masks don’t work” is the motte and “the evidence doesn’t support mask mandates” is the bailey.

What I said:

And the benefit of masks, though real, is marginal enough that I don’t think it warrants any compelled action at all by authorities (except maybe healthcare workers).

What you said:

The burden of proof is on those who would want to mandate these masks, and so far, it’s pretty sketch.

Totally agree.

I’ve been surprised at how impatient I’ve become. With my family, with my elders, with my congregation, with others (yes, even on Sanityville!) who don’t see life the way I do. Regarding covid, lockdowns, BLM and racism, politics, ethics, you name it I guess.

One would think the past year and a bit would have resulted in the practical pursuit of more humility, grace, and patience with others than it has. I’m surprised at the sin struggles manifested in self-reliance and arrogance that have only seemed to grow throughout this time.

It has not surprised me that some young, healthy, professional athletes have been vaccine-hesitant. But the fact that some of them are starting do such a great job with their public statements has been a pleasant surprise.